Inside Outside the White Cube

It’s Mother’s Day, and I’m at the opening of a new show with my mom.

She loves looking at art, though she mostly doesn’t get it and remains convinced, no matter how often I correct and refute, that: “art reflects society.”

“No Mom,” I say, less patiently than to an undergraduate in Methodology 101. “It’s not as though here, on one side, is reality, and there, on the other, is the artist, holding up a mirror to show us ‘the real.’ Art is a construction of reality.”

She nods, eager to have good phrases for her next docent tour, a fine-sounding art historical phrase or two from her professional art historian daughter. For a brief second I’ll fancy I see a penny drop as she wraps her head around this weird “construction” thing I’m trying to explain that artists do, but the penny sinks into a bog, and the next time she asks me to listen to the docent talk she’s rehearsing, she slips into the old patter as though into comfortable well-worn shoes, though there’s a fresher pair on the shelf beside her worn ones.

“Art,” she says, casting a defiant look my way, “reflects society.”

I would correct an undergraduate, but I’ve stopped correcting my mom.

I don’t like company when I look at art. A companion expects me to expatiate, to explain what it is we’re looking at. It’s hard enough to escape my own internal chatter of explanation—all the clutter in my brain about influences, movements, dates; too many too-well remembered passages in this or that canonical art historical essay that I’ve assigned too many times; too many resonances to interfere with plain old looking and seeing. That old innocent eye thing Ruskin wrote about? Art history spoiled it for me. I’m done with scholarship. I want to be personal. I want immediacy and emotion. I want to write memoir rich in the stuff of my life—my childhood and early adulthood in apartheid South Africa, the dislocations, emigrations, divorces, searchings for home, for who-the-hell-am-I? that never cease to haunt.

I press the elevator button for the upstairs gallery. I’d have taken the stairs two at a time had I been alone, but my mother’s doddery these days, fragile in more arenas than just her body, and I’m in the unaccustomed role of caretaker, trying not to fall back into feeling she’s indestructible.

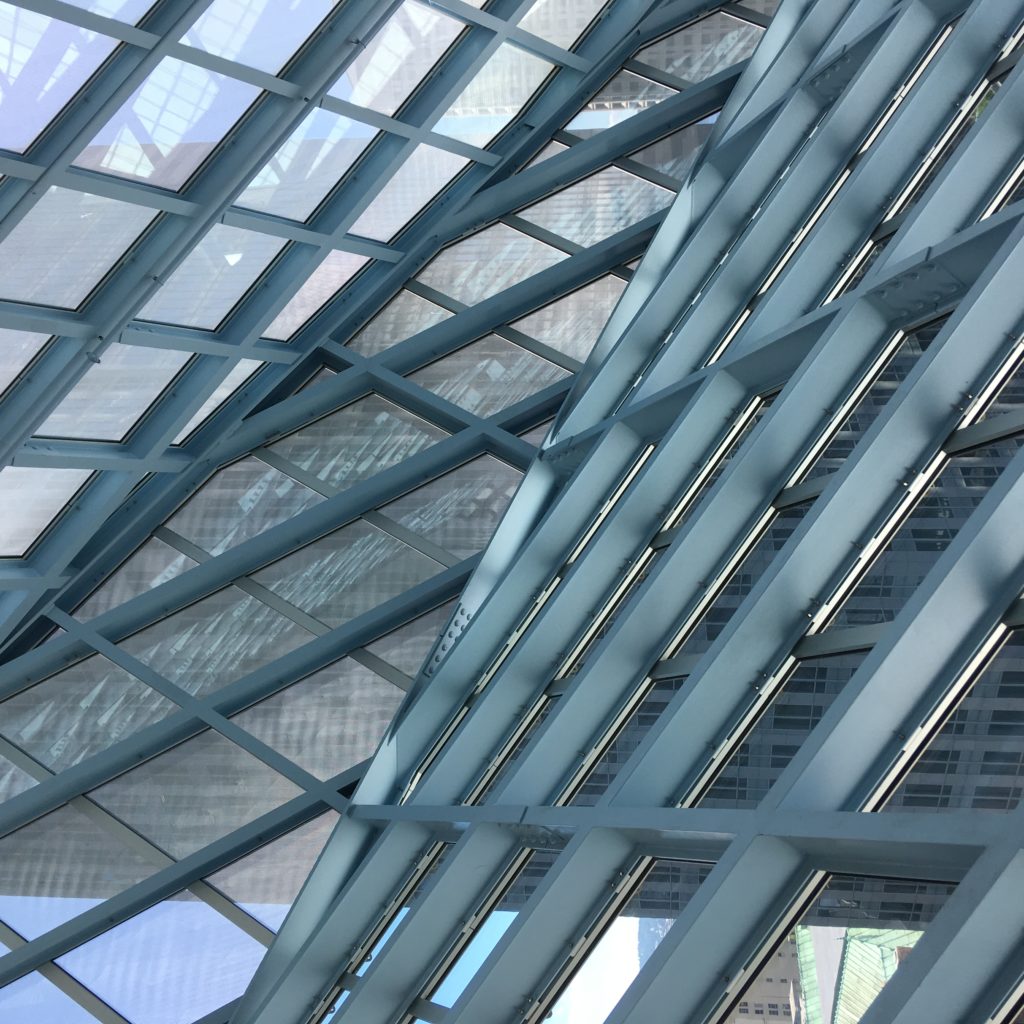

We step into the gallery. Information fills my head, presses against my temples: we’re inside the white cube, framed by the ideology of the gallery space, “constructed,” as Brian O’Doherty wrote in the pages of Artforum in 1976, 1981, and 1986, “along laws as rigorous as those for building a medieval church. . . walls painted white. . . ceiling the source of light. . . wooden floor polished so that you click along clinically. .Unshadowed, white, clean. . .”

I stand in the center, feeling on edge. My mother has her nose up against a painting.

“Jo,” she calls, “he mentions South Africa in this painting.”

It’s a large horizontal painting a la Barnett Newman’s Vir Heroicus Sublimis, 1950. She’s right to look close up. Newman wanted viewers to stand close enough to be engulfed. But this painting isn’t big enough to be engulfing,

I join her. It’s text that drew her in, draws me in. The artist, David Diao, Chinese-American, has appropriated Newman’s vertical zips. They’re not Newman’s lines—trembling signifiers of humankind’s valiant defiance of sublime terrors, but the gridded markers of a timeline: 1949-1955. Two entries only for 1949: “PRC Oct, 1949” and “South Africa Bans Mixed Marriages, Apartheid, June 29.”

South African history pours into the gallery, blood spatters the walls, shadows lurk.

Jo-Anne Berelowitz is an art historian by training and profession, now writing a memoir about growing up in South Africa during the apartheid regime. She lives with her husband and two Soft Coated Wheaten Terriers in San Diego, where she’s a faculty member at a large public university. She is currently enrolled in the MFA program in creative writing at Rainier Writing Workshop.