Ashes to Dust

El Paso, Texas

1/28/17

This morning, Mom, Ashley, and I drove up the mountain rim road, up to Scenic Drive overlooking El Paso, Texas, and Juarez, Chihuahua. We parked at the lookout area. We took the steps down to the small park below and waited for sightseers to finish their romantic moment. When they left, we walked right to the mountain edge and Mom let Daddy’s ashes fly.

His ashes were nothing like wood embers, airborne at the slightest disturbance, like flour or dandelion fuzz. These felt hefty and crunchy, more like powdered pea gravel. So, I was worried at first that they would just drop and clump up right below us, where I noticed thousands of shards of glass pointed toward the sky like a beer bottle graveyard.

But a breeze lifted right as she upended the bag. As they became airborne, the ash took on the swirling quality of smoke escaping the burning end of a Marlboro, Daddy’s favorite. The suspended ash hovered thickly for a moment, and then dissipated up and out: an ash-kite caught by the wind and whooshed toward Ranger Peak, toward the south and east, toward Mexico. Of course they weren’t all whisked away. Some coated my jacket sleeve. Some stuck to my tears. Some went in my mouth.

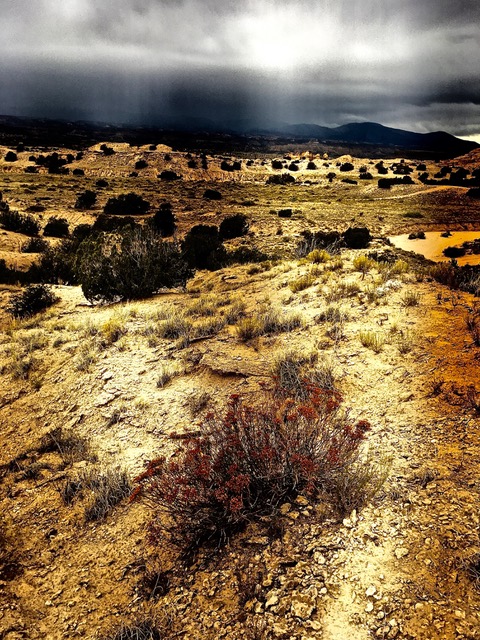

When I was five or six, Daddy started taking me out to the undeveloped desert just beyond our neighborhood. He’d set out on the rocky terrain in his powder blue F150, a single raindrop against the gulf of gravel and sand. The white-wall tires churned up clouds of dust, the only clouds for hundreds of miles. As my small frame bounced along the bench seat, I waited for the spring loaded cigarette lighter to pop up with heat, knowing that as soon as he lit up, the window would come down, and the sand would blow in, which meant tightly closed lips until we returned to paved roadways.

He would take pans of freshly-drained engine oil from the Buick or the Corvette or the T-bird or the truck and dump the tarry brown liquid right out on the ground. I watched it discolor and suffocate the dirt, leaving an unnatural blot as evidence of our visit. Once after dumping, Daddy climbed back in the truck and suggested, “Why don’t you get out and let’s see if you know the way back home? You walk and I’ll follow behind you real slow.” I knew he’d never take off without me, that he was testing my sense of direction, but this offer terrified me, and I refused to get out of the truck. I saw the spontaneity in his raised eyebrows reduce to neutral, and he slowly tapped the cinders off his cigarette into the ashtray. “Okay, princess, why don’t you just sit here in the truck and point, right, left, or straight. I’ll go whichever way you tell me.”

I run my thumb across my mouth and survey the gritty ashes clinging to my fingertip. I hear the grinding grit between my teeth and note that my mouth won’t close properly because of the tiny granules sticking to my molars.

Our morning at the mountain lookout was sunny and warm for January, in the mid-forties, but the sky was not completely clear. We could see plenty of the city and surrounding elevations of the Franklin Mountains, but everything stood beneath a thin veil of haze. As we started to detach ourselves from the observation point, I thought about the ways Daddy made El Paso a better city, about how he never met a person he couldn’t put at ease, and how the haziness seemed like a blanket of his ashes, tenderly placed over a loved one.

I realized that I had moved from before into after. Before, we chatted about trivial things:

The Bustamante’s house could use a paint job.

The new condos really block the view of the mountain.

El Paso needs rain, El Paso always needs rain.

Did you see that the Mexican Elder tree died?

I can’t believe Lucy’s Kings X is still open!

But chatting about the commonplace was not possible now. The ashes were spread. What else was there to say? We thought of stopping to eat, but I felt chalked in ash, so we just returned to Mom’s house. I needed a moment of quiet to process–to not forget–to not permit the mundane to crowd out the significant. It’s not just any day that you watch the cremains of your father kiss the city.

I miss him; I miss the chapters I lived out in El Paso; I miss childhood. I long for the honest severity of the desert, where I never questioned where I stood, always in full exposure. While I won’t stop grieving, I think I must now let go of the dust, open my grip on memory and let the sand of my childhood slip between my fingers. I believe Daddy is with Jesus, his soul lives, and the ashes are now as he, free from the sorrows below.

Andrea Dunn is from Indianapolis, Indiana by way of the Texas-Mexico border, Southern Indiana, and North Carolina. She enjoys working at home raising her three children. For decades, she wrote for her own enjoyment and growth, but has begun sharing her work, including an essay published in Entropy Magazine as well as poetry featured in Flying Island Literary Journal.